Kill Underperforming Products: Crucial for a Product-Friendly Culture

There’s a writer's term-of-art (the origins of which are murky, with claims that it was coined by Earnest Hemmingway, Oscar Wilde, or William Faulker amongst others) that goes like this: to get to the best possible outcomes, you have to be willing to “kill your baby.”

Dramatic, I know. But really, it’s that visceral flare that makes it so memorable.

In the literary world,“kill your baby” means that through the process of crafting a story or novel an author will find a turn of phrase, a character, or even a plotline that they fall in love with. That author’s “baby” was born of the genius of their imagination; it is a source of personal pride, and the author sees in it only beauty and potential. But sometimes that phrase, character, or plotline will not, in fact, help produce the highest quality piece of writing. And when that happens? The writer has to edit it out. No matter how beloved, no matter how much work went into it, if it does not make the overall work better, the author must be willing to “kill their baby.”

What has surprised me in my career working with B2B product leaders is just how often this phrase comes to mind when doing product work across all phases; product ideation, development, and management.

At any stage, a beloved concept, feature, or the product itself could fail to meet performance expectations: It does not meet the market's needs, it fails to achieve profit goals, or it distracts from a core value proposition or mission. And product leaders would be well advised to tattoo the writer's mantra into their own consciousness. They have to be willing to kill their babies. To ensure long-term success and maintain a competitive edge, product leaders must embrace the strategic practice of killing underperforming products. But they can’t do it alone.

Adherence to even the most focused personal commitment to “killing the baby” is hard for three reasons: emotional, reputational, and revenue drivers all cloud the judgment of even the savviest business and product leaders.These are profound, and often subconscious drivers of unwillingness to edit or kill products. Knowing what to watch out for is a start in helping keep these forces in check.

EMOTIONAL: The most exciting and attractive products or features will generate emotional attachment. Origination or ownership of these exciting products will only make the emotional connection stronger. Every child is beautiful to its mother. But mommy isn’t the one who is buying. Product leaders have to build in stress checks (usually via voice of customer testing) to assess if the market finds your baby attractive.

REPUTATIONAL: Even when product flaws are recognized, admitting to flaws is deeply threatening. If the product originator or owner has dedicated significant time to the development, maintenance, and even advocacy of the product, conceding “defeat” when they have prioritized their time and resources could undermine the credibility. It throws their judgment into question, and could even limit their career potential if product success is synonymous with personal success.

REVENUE: Sometimes a product is making money. But not as much as expected, promised, or needed to meet organizational objectives. Killing it, while the right decision for the organization, would immediately stop that revenue stream and no one is keen to say no to ready revenue. At the same time, longer term investment in more profitable areas often feels too abstract and remote to satisfy relentless quarterly revenue objectives. But continued investment in a product that does or will underperform will consume resources better directed to more profitable work.

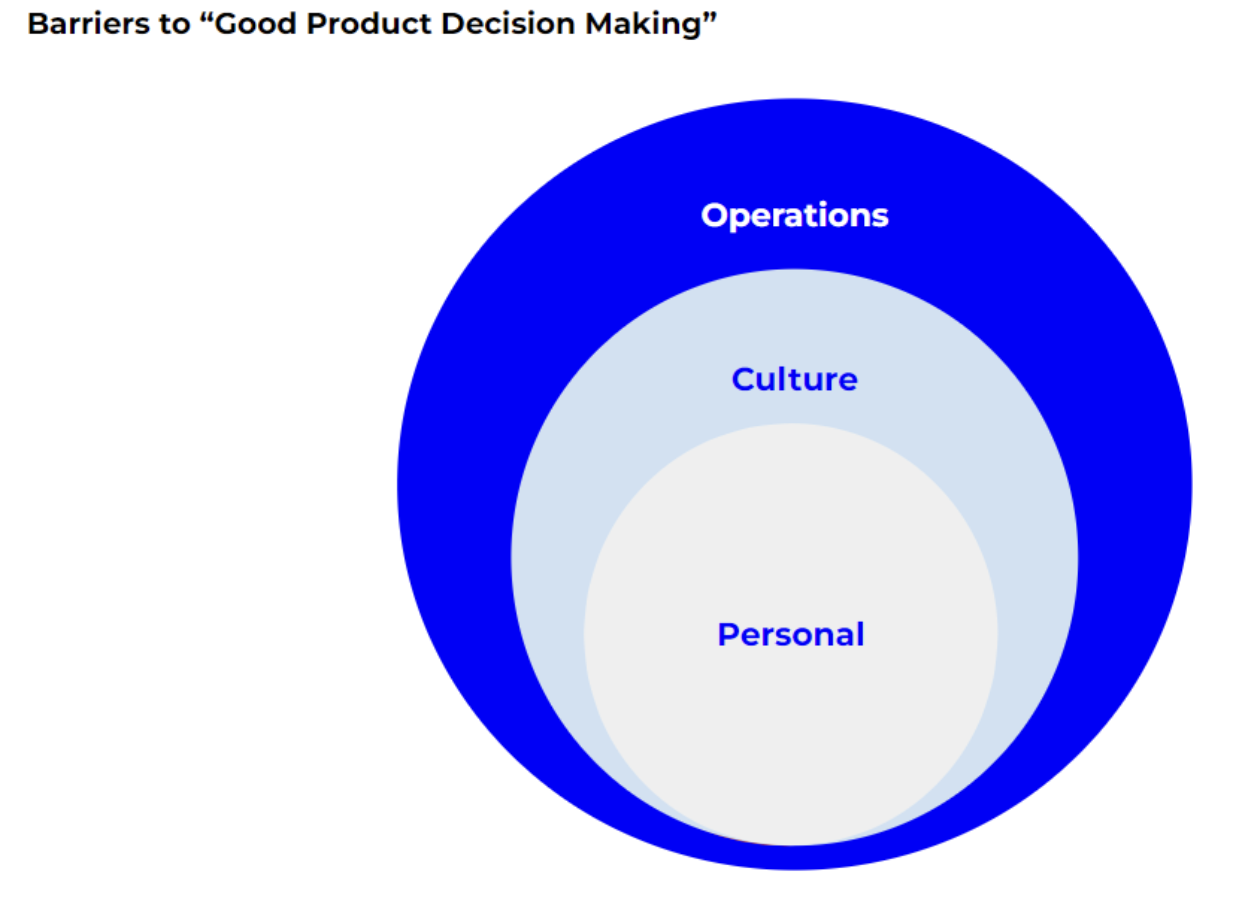

Building the fortitude to kill underperforming products requires an understanding of these drivers, and can be solved through three levers: personal, operational, and cultural.

The fastest way to ensure that personal reluctance to kill underperforming products is to shift the focus from making a great product, and instead to making good product decisions.

Interestingly, a significant portion of personal barriers are a subset of cultural barriers: the fear of losing face when your product has to be killed is best addressed when the organizational culture does not conflate personal and product “failure.” A product can fail to achieve the hopes and dreams of the organization, but that is a product failure. Not necessarily the failure of the leader. A product leader only truly fails if they continue to throw good money after bad, and succeeds if they instead are able to direct their resources more effectively. If the culture is able to make that distinction, the product leader is more likely to make a decision without fear of risking a reputational hit - the organization will judge them favorably for making good product choices, even if that choice is to kill the product.

And even more compelling is the fact that corporate culture is really a product of the organization's operations. You can tell a product leader how important it is to “make good product decisions” and be willing to kill the baby, but if his bonus is attached to the product’s success, if his performance metrics are aligned to product success, if his career trajectory is focused on product success - and not good product decision making - he will never be ok killing the product. He will fight to keep it alive and going, even as it is the wrong decision for the business.

Organizations who want to build a strong product-friendly culture need to reckon with the fact that the operations and culture need to change in order to sustain an environment where it is ok to be like Hemmingway; one where product leaders are willing to “kill the baby.”

Best Practices to Build a Culture that Prioritizes Good Product Decision Making

- Define Product Leader Success based on “Good Decisions”: Develop a set of product performance metrics that are aligned to appropriate and leading indicators of success based on the maturity of the product. Build a separate set of product team performance metrics based on good decision making about their remit. Do not conflate the two.

- Be Transparent About Product and Leader Performance Expectations: Provide clear explanations to stakeholders about the criteria to sustain or retire a product. Socialize that product leaders’ primary objective is to support high level organizational goals via good product decisions. Ensure that teams and leaders understand that personal and product performance are not the same thing.

- Continually Evaluate Product Performance: Implement a continuous evaluation process for the product portfolio. Ensure that decisions about product investment are iteratively reviewed to course-correct for early indicators of outsized success or potential weaknesses. Don’t use lagging indicators which will hinder agility in responding to product performance. This proactive approach ensures that underperforming products are identified and addressed promptly, enabling fearless product investment decisions.

Killing underperforming B2B products is an essential strategic move for businesses aiming to maintain long-term success. But too many organizations have underappreciated the personal, cultural, and operational barriers to making the best decisions. By making adjustments to how you measure product and leader success, and supporting a culture that prioritizes “good product decisions” (even when that requires you to “kill the baby”), organizations can better optimize product resources.

Vecteris' Productization coaches are experts in guiding you and your organization along the product innovation journey. We can help you make an informed decision if, or when, it is time to kill a product and pivot. Please reach out to learn about how our Productize Pathway® Advisory Solution can benefit your team.