What Summiting Mount Kilimanjaro Taught Me About Overcoming Fear

One of the most rewarding parts of my job is helping people overcome fear. I help clients overcome the fear of uncertainty as they try to innovate and develop new products. I work with my team to overcome the fear of not being liked when they have to deliver unpleasant market feedback to a client. And my co-founder and I talk a lot about our own fears of failure as we try to grow, but also protect, our business.

I’ve also watched brave colleagues, friends and family stare down fears when the stakes are much higher - a cancer diagnosis or a sick child, for example. And I think of their ‘fearlessness’ when my smaller work-related fears can feel all-consuming.

This summer, I had the opportunity to practice fearlessness in a new way. On August 3, I summited Mount Kilimanjaro with my 16 year-old son, David.

I had been dreaming of a trip like this ever since I discovered that my son likes hiking *almost* as much as I do. Reading Michael Easter’s book The Comfort Crisis, helped me realize that a trip like this would not only give me an opportunity to get closer to my son but it would also take me way outside my comfort zone and help me strengthen my fearlessness muscle.

Although hiking Kilimanjaro is accessible for many fitness levels–technical climbing skills are not required, and experienced guides are required by Tanzanian law--it is NOT a zero-risk endeavor. So while I was excited, I also harbored a variety of fears. In the months leading up to the trip, I worried a lot about getting hurt or sick on the trail, especially suffering acute mountain sickness (AMS) from the high altitude. I feared that I would fail to reach the summit (fear of disappointment and embarrassment), and I feared travel snafus like missed flights and lost luggage, and of the whole plan being called off thanks to a positive COVID test. “What if…?” became something of an unhelpful mantra as our departure drew nearer.

Fortunately, I realized that I could use the same fear and risk management practices that I coach–and watch successful leaders exhibit every day–to help us climb Kilimanjaro. Those practices include:

- Think big, but start small,

- Mindfully focus on risk you can control,

- Expect less than perfect,

- Ask for help, and

- Practice gratitude

Think Big, Start Small

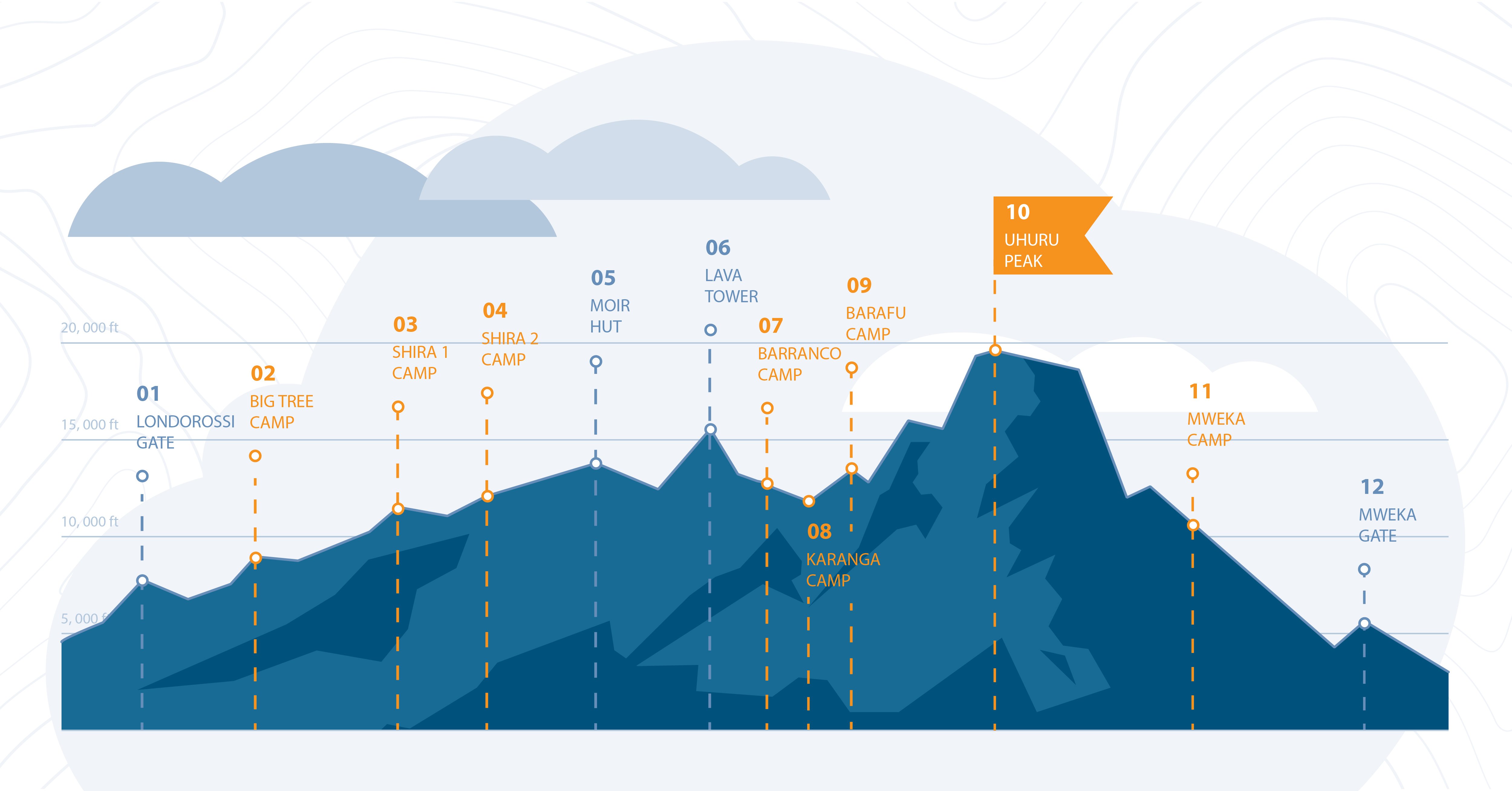

The phrase “pole, pole”--Swahili for slowly, slowly–is part of the Kilimanjaro culture, for good reason: the more days you spend on the mountain, and the slower you progress upwards, the better your chances of a successful summit. The best guides insist on hiking slowly–between 7 and 9 days on the trail–and ending each day at a slightly lower elevation than the group’s highest achieved point for the day (“climb high, sleep low”).

For those of us who are accustomed to thinking about progress as linear, this advice can feel frustrating, much like the advice I give clients to “think big but start small.” I consistently had to remind myself of what success looked like for this experience–and even though I knew I needed to come back down the trail to feel my best and reach a new elevation gain the next day, making so little perceptible progress felt a little bit like failure.

Mindfully Focus on the Risk You Can Control

It is easy to amplify fear by disproportionately assessing risk. Focusing on everything that could go wrong can be paralyzing.

A case in point: my reading list for this trip was almost as towering as Kili itself.(I love to research!) I consumed piles of memoirs, blog posts, and videos in the months before the trip, but as time wore on, I found myself growing fearful about any and every negative outcome or scenario. Would one of us get altitude sickness and faint on the way to the summit? How would I manage a week of sleeping in a tent? What about storms and lightning strikes? Rock slides? Lost luggage? Blisters? You get the idea.

What started as a desire to learn from other's experiences went way too far, similarly to how some organizations may go down a rabbit hole obsessing over what their competitors are doing, as opposed to focusing on their own unique strengths and advantages. As information-gathering turned into obsession, I recognized what was happening and stopped reading. I then mindfully refocused on what I felt I personally needed to do to prepare given my capabilities and David’s capabilities. For example, we are both already fit and experienced hikers, and we were sticking to our training schedule. Our largest risk was driving each other up the wall while sharing a tent for a week.

Expect Less Than Perfect

Part of fearlessly climbing Kilimanjaro included expecting less than perfect and quickly bouncing back from mistakes. For example, on the second day of the trek we had a steep climb and were ascending to more than 11,000 feet in elevation. In the middle of the hike David said he needed his inhaler, but it wasn’t packed in his day pack. Our guide had to radio ahead to our porters to bring his inhaler back to us. I felt like the worst mother–how could I be this unprepared while bringing my child into a risky environment?

Really, it was no big deal. David was fine. My guide reassured me, no worries, “hakuna matata.” And I had a moment where I had to confront my own expectations of what a “perfect” mother would have done in this scenario (as if she even exists!) and instead focus on what really mattered: doing what it took to safely experience the hike with my son, get some incredible one-on-one time with him, and to enjoy ourselves along the way.

Ask for Help and Invest in What You Need

I sought help at every turn while preparing for this adventure and on the trail. The support of expert guides is invaluable–and required by Tanzanian law to scale Kili–and there were so many times on the trail when we needed help with equipment, navigating tough terrain, adjusting our expectations, and staying focused on our goal.

I have to admit: part of my risk management/anxiety reduction strategy for Kilimanjaro was to over-buy. My REI store knows me by sight now, and I left for my trip with no fewer than seven prescriptions for in-case-of-emergency antibiotics, anti-nausea meds, and an anti-inflammatory should one of us develop edema.

I have since reframed my over-buying as a form of asking for help: seeking the advice from experienced hikers, gear experts, and my physician helped me understand what my personal needs were, and how to address them. Their input helped me understand where to invest resources for this trip–planning more nights on the trail to support acclimatization and ensuring that we had enough warm layers–and was necessary for success.

And a hard lesson from my business and product development experience hit home here: if you are not willing to invest sufficient resources into achieving your goal, don’t do it.

Practice Gratitude

When the hike became challenging, or my fears overwhelming, feeling gratitude for the journey itself, rather than focusing on the summit, was a powerful fear-buster.

David is a typical 16 year old: growing up fast, trying to figure out who he is, and eager to exert his independence. The time we spent together training for the trip (four months of weekly long hikes) and hiking phone-free for 8 days in the mountains was priceless. Watching him summit Kilimanjaro is an experience for which I am incredibly grateful. I was inspired by his willingness to take on this challenge and face it fearlessly. Pausing to be grateful for this once-in-a-lifetime bonding experience with my son kept me focused and able to hike through discomfort and fear.

The Good News: You Can Train to Be Fearless

On our flight to Tanzania, I serendipitously ran across a recent LinkedIn post by Joe Terry, CEO of Culture Partners, that spoke to the heart of this adventure on Kilimanjaro. Reflecting on how our innate human desire for comfort keeps us from growing, Joe wrote compellingly about when we deliberately step out of our comfort zone, we acclimatize our minds and bodies to handle the unexpected. Taking on challenges–which can be as small as actively listening to your co-workers or family when you are tired or as big as hiking to the top of a 19,000+ foot mountain–builds your resilience to adversity when we encounter it.

Fearlessness works similarly: when we consistently practice it in one area of our lives, it makes it easier to be fearless in other areas. When David and I reached the summit after a week of self-imposed adversity, I couldn’t help but feel simultaneously strong and humble: confident in my ability to do hard things and more in awe of the effort required to do them. We are indeed so much more capable than we think we are, and sometimes, we need to stretch our boundaries, face our fears, and become uncomfortable in order to see that.

If you are thinking of climbing Kilimanjaro, please reach out. I would be happy to share more lessons learned!

I am also planning a 5-night trek in Peru in June 2023. There are a few spots left and I would love for more kindred spirits to join. Reach out to me for more details if you are interested.